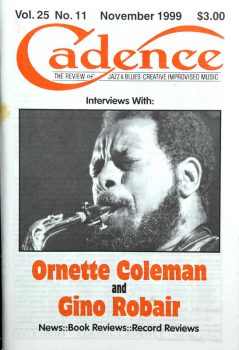

ORNETTE COLEMAN: INTERVIEW

ORNETTE COLEMAN

P.O. Box 1189, Triboro Station, New York, NY 10035 USA

BUSINESS PHONE: 1-212-831-7738

dcharmolodic@earthlink.net

Tone Dialing:

A Conversation on Friendship with Ornette Coleman

This interview was conducted by telephone from

Paris to New York on 15 August 1997. The transcript was made by Pamala M. Terterian

on 27 August. ©Clara Gibson

Maxwell 15 August 1997. Originally published in slightly edited form in

the jazz magazine Cadence (November 1999).

clara gibson maxwell: I'm interviewing you about friendship.

ornette coleman: Oh, that sounds right.

clara gibson maxwell: I thought it was sort of appropriate.

[laughs] It's funny, I've been preparing for this like it was a rehearsal

or a performance. I took a long bath. [laughs] So, tell me . . . well,

let's start with us.

ornette coleman: Sure.

clara gibson maxwell: How do you see collaboration's interface

with friendship?

ornette coleman: Well, I'll tell you the truth, I always thought

it was one and the same. I mean, when you say "collaboration," that's a word

that describes something you are doing, that you're trying to achieve and you're

trying to help someone [else] to achieve--something you are going to do with someone. A quality, a quality of work that you want to share with another person.

And I think that, as we talk, every time I see you we're always doing something

like that anyway, as far as the tone

dialing of it.

clara gibson maxwell: Oh yes.

ornette coleman: But--remember the man I met with you in Pittsburgh?

clara gibson maxwell: Yeah.

ornette coleman: Well, I saw him [David Stock, Artistic Director,

Pittsburgh New Music Ensemble] at one of my Juilliard recordings--maybe there

was someone there that he knew. And we were talking about you. I said to him

that you are so well versed in the quality of what you believe that I never

thought about doing anything with you lesser than the way you wanted to do it,

and that you have been striving to achieve a certain perfection in what you

believe, and that you were eventually going to do that. So he said, "Yeah, that's

right." I was trying to say [this] to him because I knew that when we met him,

there was some connection to what his relationship to those things was going

to turn out to be.

clara gibson maxwell: Uh-huh.

ornette coleman: But I think he was . . . he's either a director

of a performing arts society or something like that.

clara gibson maxwell: Yeah.

ornette coleman: Uh-huh. Well, he sounded like he was still

interested in what your projects were.

clara gibson maxwell: Uh-huh.

ornette coleman: So when you just asked me about those kinds

of things. . . . For instance, I had called several musicians in my age bracket

that I wanted to share "harmolodics" with. . . . All of a sudden, some of them

got sick, and some of their managers explained to me that they had other projects

right now, they didn't have time to get involved with another one right now.

None of them--well, they all said they were interested in working on

the project with me. I haven't given it up, but I'm not pursuing it. It's too

intense. I haven't gotten enough inspiration to do it. But [it's] one of the

reasons why I think that particular word "collaboration" doesn't spell out the

actual involvement or results of what people do that do get together--the quality

of what one is trying to achieve. Like in my case, the only time I get to collaborate

on something is when someone is hiring me to do something that I represent in

the entertainment business, [something] that has to do with music. I've been

trying to get in a position where I can be consistent, to do the things I do

consistently, but the more I find the time--the more I get involved in trying

to do those things--the more I realize it takes up so much time to get to present them. And in the last, oh say, the last ten years, maybe I've worked on three

projects, and each one of those projects took maybe three years apiece--and

[for] only four days or three days [of performance]. So . . . my sense of collaboration

is not as fulfilling as how I would like to have it done, because I think it's

something that, if you have success at it, it should seem to be easy to do.

But in my case, it doesn't seem like that--it seems like the more success I

have, the harder it is to do again. I don't know if I'm explaining--if I'm answering

what you asked me about collaboration.

clara gibson maxwell: Yeah, I think you very much answered

it. But, on some level, it seems to me, what we're doing--in a kind of educational

way--is talking together about what we do and experience. And it seems to me

that at a particular time in your life, when you were shunned by a whole lot

of other musicians, you did have an opportunity to have Charlie Haden and Don

Cherry around, and an opportunity--even though it had absolutely nothing

to do with the profession--you had an opportunity to play and exchange ideas.

So I was wondering if, on the business of being shut out, didn't that also give

you an opportunity to find your voice with the people who could follow

you? With what you were doing?

ornette coleman: Ah, well . . .

clara gibson maxwell: --Or am I idealizing something that I

didn't live through? [laughs]

ornette coleman: I think you have your [finger on the] pulse,

on the philosophy of the experience that I have been having since I left my

hometown. In each case, all of those things that you've spoken about happened

basically from the environment--being at a certain place at a certain time.

And the other [thing was] finding people that were going through something that

I was going through that made them interested in it. But my problem is that

I have never been able to offer any consistency of performance.

When I came to New York [in 1959] with Charlie and Billy

[Higgins], it was at The Five Spot. The Five Spot, as I knew it, was a class-C

place, according to the fees that they have to pay you for playing in a class-C

place (I think, at that time, $96 a week). And, you know, when you live in a

hotel that's costing you $150 a week, it doesn't seem like you're making too

big a profit. So the point I'm trying to make is that economics and art have

never been good companions, and certainly haven't been good companions for me.

All of the things that Denardo has helped me do since he's been my manager,

basically . . . we've never made any money. We've always had to put the money

into it. If we said we wanted to jump off a bridge without a parachute so long

as somebody at the bottom was going to catch us, that person would say: "Okay,

I'll make it safe so that when you jump, you won't hurt yourself." Whatever

it costs you, that's what you're in for. It's more like what people do in, I

guess, Communist countries (or Communist philosophy), where someone gives you

an opportunity to do what you do, but the idea of making a profit from it .

. . . And yet, I think that--I know that--your insight is right, but

your insight is closer to what I'm speaking about, more than [to] the idea that

it's happening because of opportunity, time, and value--it's not happening because

of those things--

clara gibson maxwell: --Yeah--

ornette coleman: --It comes out of a condition that presents

itself in a way where someone is there to support the philosophy of what you're

doing in their way, but [moving] from what they do to your next experience has

to be conjured up in another total way, and only what you find--only who you find to do that in the next event--is the only way it's going to happen.

Doesn't matter, you know. . . . Whereas in the real consistency of arts entertainment,

where someone, I mean like a conductor--you know, a conductor goes, and he's

at the Philharmonic for one season, maybe he'll go to Chicago for another--but

dance and performance are not like that.

clara gibson maxwell: Yeah. So it sounds like what you're saying

is that having a career and having a vocation are not necessarily the same thing.

ornette coleman: Yeah, that's right. Neither are filling in

lots of forms and opportunities for foundations. [They don't] respond that same

way. It seems to me, in Western culture . . . I don't know if it's true of .

. . I've been to Japan, haven't been to China. . . . But it seems to me, in

Western culture, it's that what determines news is what everyone in the business

of helping artists--see, they're moved by the image of their relationship [with

you] in the press, and if what you're doing doesn't fit that image, they don't

take too much of a chance with you, regardless of how good you are, you know?

That has seemed to be my case lots of times. But, ah, one of the reasons why

I got involved with trying to do more things on a multiple level is because

of the very thing I'm speaking about--because I realized that, having your work

and everyone else's work, there is something that someone can be doing that's

on the same level [as] what you do. In fact, I was telling someone today that

there are lots of people performing music that improvise what I'd call jazz,

and so therefore if you are a certain race and you are playing a certain music

and you fit that image, then they call what you do jazz. But there are lots

of people playing music that improvise in the same way as people that're called

jazz, but they're not called jazz. So all these things that you are

mentioning--it's basically based on two elements: one of those is the creative

element having to satisfy the over--ah, what's the word?--of having to offer

the opportunity to creative people to find themselves in many different environments,

but the quality of what they're finding is only making what they're capable

of doing more perfected, you know? And I haven't been around in your environment

to see how you're surviving what I'm speaking about, but when I do hear from

you or talk to you, you sound like you're just as intense about what you're

doing as [I am about] what I'm doing.

clara gibson maxwell: Yeah, yeah.

ornette coleman: Is that right?

clara gibson maxwell: Yeah, well, it sounds like--it's also

the irony, you know, after you get over the superficial feelings of jealousy

and sadness about oh, so-and-so has the gig, I don't, or, the project

will never happen. I mean, in a way, the fact that our project hasn't gotten

off the ground, in a funny kind of way it's been a blessing because

it's had me have an opportunity to really, really experience the friendship part of it, and the collaboration is something that--it's the weirdest thing,

it's like it gives me so much. I guess my question is, what is it about being

able to experience something with another person in a collaboration such that

you become so trustful of something that's bigger than yourself that it suddenly--there's

something about having that mirror and that love that makes you believe in yourself all that much more? And I can't call it faith, because that would imply some

kind of dogma, and there's nothing philosophical, or, there's no thought in

this--it's really very, very primal--it's about being able to really love and

trust.

ornette coleman: Well, you know, I hear that in your voice.

I've always heard it in your philosophy of creative thinking. The thing that

is amazing that I admire about the way in which you express yourself through

the things that you believe is that the reality of quality doesn't

have to be lessened because of something you can't do that others don't know

about. But the idea that you do know about the quality that you are and that you want to represent--that that quality does exist because you exist. And because it exists, you have a clear idea of how you

would like that quality to manifest, whether it's in your clothes or in philosophy

or whatever. And you are not trying to put that quality in any kind of jeopardy

whatsoever because of time or opportunity. It's like what you're saying about

friendship--I know that, I know you're right, and I feel the same

exact way. The only thing that I haven't done in relation to my friendship

with you is that I haven't started out getting you involved in something other

than what you have tried to do because--

clara gibson maxwell: --Well--

ornette coleman: --because I always thought it would be better

to wait, to start with the thing that you would like to get me involved in.

I knew it would happen--

clara gibson maxwell: --Yeah--

ornette coleman: --because, you know why? Because I really

believe that the idea that you would like for me to participate in your work--it's

that if that came about the way you wished it to, it would fulfill something

that I could experience--that you are experiencing and that you already know

about.

clara gibson maxwell: Yeah.

ornette coleman: And it seems to me that I am not in any way

avoiding the moment for you to have that experience. Believe me, I'm not trying

to get in your way or trying to guide you in any way about how we should do

it to have it done as you wish. But I do know this: that it's got to get more

and more clear in your mind about the results you want from it in relationship

to the public expense. And to me--you know, I'm not you, so I don't know what

that is, but I think you know it--to me, that's the only thing I really

and truly understand about artists and creativity, and the Bible, and all of

these things. Because there are lots of things that I have thought about that

I would like to do with others, and I've tried it, but I haven't had as much

success with that. I mean, when I call up Sonny

Rollins or Keith

Jarrett or someone--I like Keith Jarrett and I have called

him, and I wanted to share it--but I've found that we can't speak about it--I

can't speak to them the way I'm speaking to you. When you speak to me about

something, you know, I'm a human being first and a musician second. . . . I

really accept every person that is interested in something that I'm doing, something

that they're doing that they want me to be involved with, for collaboration.

Ah, I am never going to say, I don't do that anymore, I'm not interested,

or whatever, because I find more and more that [when] creative people build

monumental values around themselves, they no longer are as exciting as those

values and trends are. I think it is really fantastic that you are dedicated

to what you believe, to the quality of what you believe and not looking back.

And that's very, very healthy.

The only other thing is that--once you showed me something

on the [video]camera--maybe it's been two years now or more--one of your performances,

and I remember you were telling me about other things that you have done, but

the main thing that blows my mind is that your art seems to be more clairvoyant

in a psychological--in a physical sense as well as a mental sense--

and one enhances the other without any time lapse in relationship to how true

you can express it when the opportunity [arises] for you to have all the components

that you wish to have to do it. It's in your voice. You express it

all the time, you know. So, I would rather think that, as human beings, that's

what--that when we are talking the way I'm speaking to you now--it's that that

quality is still as alive, that it's still activated at this very minute. Then,

how you conceive it to be, what it should be, the title of the movements, might

have advanced, but the quality of what you are continuing to do is

real at this very moment [when] I'm speaking to you. And, you know, the only

thing that you have asked me to do is the piece you were showing me, Choros.

Now, has that grown larger for you, or wider, or what?

clara gibson maxwell: Well, it's funny. It always stays in

the back of my mind. In a way, it's sort of about what we're talking about now,

insofar as it's about how one's love of oneself is so much about one's love

of community and what community makes, the way in which you don't exist--at

least, my own feeling for myself is that I don't exist except to the extent

to which I can both give myself to myself and give myself to other people. This

is a gift of the Athenians--this is the specific gift of the birth of democracy

and the birth of philosophy in Athens: people for the first time imagined that

they could make humanity in their own mind, but they also realized

that if they were going to self-institute the rules, then they also had to change

them [laughs] as they go along.

Ornette Coleman: Yeah, I see.

Clara Gibson Maxwell: In other words, it can't be one thing

all along, but it has to be a continual questioning of that. And that's what

improvisation is, in the sense that it is the capacity that when you--when a

principle is good enough it's flexible.

ornette coleman: Uh-huh, yeah, that's right, that's right.

You know, you sound so clear in how you present the qualities of life that you are as well as what you've experienced. Oh man, it's just fantastic

the way you--I mean, it's almost a voice that creates images of what you're

saying as you talk. It's really fantastic. You know what? I'm trying my best

to find how to get close to those qualities, without thinking about my needs

all the time, and it's very hard, very hard to do.

clara gibson maxwell: Yeah. Well, this is an odd question that

comes out of this, though: How did you handle envy and jealousy? Because the

problem is that when people have an experience of freedom, I mean, frankly,

it freaks them out sometimes.

ornette coleman: Yeah, that's true. Well, the first thing that

I realized in myself is that, you know, in the language of human beings there

are lots of words that sound like what they sound like--I mean, there are a

lot of words that defend what they sound like to people's ears, to

make them get an image or an attitude. But there are also lots of words that

sound like it's something that, if you allow it to have it, it has a certain

meaning to using the contours like that. But in my case, I am often--I was just

talking today to someone, and I was saying, "You know, there are lots of people

now in America that are African American that had to have their names changed

in order for them to become American, and yet there are lots of non-African

Americans that changed their names for the same reason." You know? But yet that

didn't make it even, that didn't make both of them equal. So, when I think of

that, then I think of words having--or not having--the same equal thing to everybody else. I mean, when you speak of the word "jealousy," the jealousy

between someone having something that someone [else] doesn't have--the jealousy

of someone who doesn't have is one thing. Speaking of someone as jealous

because there is something a person can do that another person cannot do, that is a form of life, you know--hatred with jealousy. So, to

me, the basic things that I have always responded to have not been from jealousy

or need or want, but from sharing. And, even in sharing, maybe there's someone

that always wants more or less than someone that you are sharing with, but the

main thing, as you've said before, is that love has no container--you can't

have a cup of love, a barrel of love. So, let's assume that love is a word,

that it's a code, for "eternity." Right? I mean, there is nobody that

would not never like to be in love. So you would assume that, if love could

exist, it could go into eternity. So, yes, I have not met anybody that has said

the reason they are living is because they're living in eternity and that makes

them love. But I do believe that if eternity could exist in the form of something

that you could feel and believe, it would have to be in the form of love. And

the thing that art and creative people do is to remind people of their history

of those moments. The present is the only thing that can sum up the past and

the present and the image of the future. But the problem with love is that whether

you see it or feel it or touch it, it is not something that you can contain,

it is always something that you have to share. And I have been trying to figure

out how to do that without taxing other people. But, you know, to be intelligent

or to be illiterate or something, sometimes I think love is seen to be as if

it's being cloned. You know? And I don't think you can clone love.

clara gibson maxwell: No.

ornette coleman: No. So I think that's my answer for jealousy--that

you can't clone love.

[chuckles]

clara gibson maxwell: It was only after knowing Denardo for

a long time, and meeting Jayne

[Cortez[, performance poet and Ornette's former wife] when she was on tour

[in Paris, performing with her son Denardo and their band, the Firespitters],

that I realized, part of the reason I get along so well with Denardo is because

in many respects we were brought up in a lot of the same ways. I mean, I can

remember vividly, in the late sixties and the early seventies, my parents getting

into all kinds of trouble with people in West Virginia because they took me

to [artsy, X-rated] movies , and my sister was arrested. . . . I guess I've

known Denardo for maybe, I don't know I've known you guys for seven or eight

years now. So, much of what Denardo and I seem to have in common is, "Well,

actually, we ended up turning out fine, we're really remarkable people.

. . . All the beautiful things our parents gave us . . . and we're beautiful because of [laughing] all those beautiful things," [all those

defining moments we've lived through].

It makes me think of the way that people idealize [or vilify]

moments [like the sixties, for example] as being this or that but when you're

actually living through them, it's so completely different than what

it is that people talk about. So, in a way I'm really grateful that we have

an opportunity to actually talk about our friendship, because we're

talking about an experience [a reality rather than an ideality]. I

hope very much that all of this comes through.

ornette coleman: I want to ask you. I don't have any knowledge

of how politics work. Maybe I've--have I ever . . . ?--I've voted,

but I haven't actually been involved in the everyday life of someone that's

living to bring a certain political image to their community or to the world

or whatever. But I find that there are lots of artists in America and in certain--I

think maybe in Europe. . . . For instance, in Europe, if a person comes up and

says something to you about how "I like your work" and starts talking to you,

I mean, it's very common for someone to say, "You know, I'm Communist, but I

like your work and I wish I could get you to come to my school." I have never

had anyone in America walk up to me and say they're Communist and treat me in

a way where they were interested in something I was doing. But I have seen a

lot of people that didn't say that [but] that wanted me to respond

to them as if they were. [Clara laughs]

It's always bothered me because, you know, you have these

different categories in America--you have rock, you have country, you have jazz,

and you have Western--but they're played by the same people. So, I mean, you

never see a rock musician saying--I did see once where some young rock

kid said, "I like John

Coltrane" or someone--but you never see any successful people in

different categories going in[to] an[other] environment--I mean, you never see

anyone that's selling millions of records, like I think [a musician] once told

me that he had some relationship to Kenny

G, but it didn't have anything to do with Kenny G sharing his success or

his audience with him, it was more that he was sharing his presence of being

successful with him. The reason why I'm saying that is because I find that,

every day, instead of running into people that you want to do things with and

that you can do things with that are valuable to you and to them, you'll find

that you're running into some sort of territory that represents a certain image

or attitude--[you'll find] that this environment is trying to rise above the

other environment. And if they can get you to join what they want to do, then

it makes them stronger. And, ah, it doesn't matter what category it is. When

you realize that, if that's true, why is it necessary if everybody is still

doing the same thing?

clara gibson maxwell: Well, I don't know. It's really--I hope

this doesn't sound like something that doesn't come off in an interview--but

being yourself in the deepest way possible is connecting yourself to the community

and is really being the political statement, if you can do it in a way that

[works]. Because I've seen it in you, and I've seen it happen in other people,

and, little by little, I've kind of seen it happening in my own world. But it's

very hard to see it in yourself because nobody has that kind of perception about

themselves. And if they do look at themselves that way, well, maybe

they belong in a Calvin

Klein ad anyway. [laughs]

ornette coleman: Yeah, the reason I was saying that is because

as long as I've known you, I have not seen--I haven't been out with you and David [Ames Curtis] at a dinner, or seen people that are your friends or that you like to be around--or

whatever you enjoy about living in relationship to your art, or what your environmental

opportunities are, as far as the territory that you find yourself in. With me,

unless I'm playing, I don't have that. So, finally I realized that maybe we

are both in the same boat. But the thing is, I actually think that you are visually much more realistic than I am. Because when someone gives me a chance to exploit

me--and what I mean by that is, they say, "Would you like to do this?" Or, "Do

you want to do that?" And I say, "Fine, yeah, let's do that"--it's not that

I can just call up and say, "I want to do this," and someone says, "Oh yeah,

we know we are going to make money." Something interests you, why not? It took

me a long time to [yawns] . . . . They've consented to do what they've

done. And the jobs that I've had in Paris--I've been speaking [to people] for

years or months to do those things.

But, you know, it's not just playing the saxophone or writing

music that I'm interested in. What I'm trying to do is to involve any person

that can express or wants to express something that is equivalent to what they

believe in, in the environment that I'm in. I want to share that environment

with them. But the thing that I can't do is, I can't have the kind

of success that will make it consistent. It always seems to have a Communist

or political attitude, or like, "Oh, we're giving you the money just to do this

and get you out of the way."

clara gibson maxwell: [laughs] Oh yes, oh yes. . .

.

ornette coleman: That's not right, because that's not the attitude

that I'm--that's not the reason why I'm trying to do what I'm doing, you know?

The reason why I am saying that is because I think that one of the biggest problems

that follows your career is that not only do you know what you want to do and

how good you could do it, but the moment you explain to someone what it is,

that's the one thing they don't want to do for you. [Clara laughs]

It's crazy, because in fact if someone asks you what you're doing and what you're

interested in doing, and you express it, it's because you think they're interested

in supporting what the quality of it could be if it could get done. But instead

of that, they just want to know how to sabotage it so it makes sure it won't

get done. [Clara laughs] And the thing about it is, it's not natural

for that to be the conversation of the moment when that moment has a fulfillment

to something that's alive and valuable. I haven't spent lots of time around

you, but from the way that you express yourself, if you express yourself the

way you express it when we're talking to someone else that's in the

field of entertainment that would be interested in relating to you as a human

being, they're probably too afraid to get involved with the depth of what you're

wanting to do because they're not prepared for the results. You know? And so

therefore they just pretend that you are from another planet or some other thing.

But I think you should never give up what that is and [should] perceive any

moment at any time [as the moment] to make it a reality. For instance, you know,

the people at Lincoln Center, why couldn't you--I mean, whatever you would want

I could do--I mean, they could do that there--they're having that festival every

year. . . .

clara gibson maxwell: Sure, sure. Well, as I say, for as long

as I have you as my friend, irrespective of whether you're the composer for

the piece [Choros] or not, I'm sure I can do it. And, definitely, we'll

look into it.

I think that this does it. So, this has been just beautiful!

ornette coleman: When you and David come to New York, I'm going

to take you out to dinner.

clara gibson maxwell: Okay, all right. Well, I'll be back in

touch about some other stuff. By the way, did Skip Gates ever get in touch with

you and send you his journal [Transition]

? This is Henry

Louis "Skip" Gates, Jr.?

ornette coleman: I've heard of him. Didn't he put a book out

about Blacks and Jews? No, that's not the guy. . . .

clara gibson maxwell: I don't think so. He's done a whole bunch

of stuff. The managing editor of his journal calls up and says, "Hello," and

I said, "Hi," right? Then he says, "I want to talk to you [about] Ornette Coleman

. . . I want him to review the new Sun

Ra biography." And I laughed. There's some sort of backhanded compliment

in it. It's that Ornette is now officially consecrated, so we can have him write

a review of Sun

Ra so that now Ornette can make Sun Ra respectable.

ornette coleman: Oh my goodness. Well, I don't think they have

to do that to him.

[Both laugh]

©Clara Gibson

Maxwell 15 August 1997