Welcome !

|

|

WWW.KALOSKAISOPHOS.ORG

is the website of Mon Oncle D'Amérique Productions, an

"association loi 1901" based in Paris presenting the

artistic collaborations of American choreographer Clara Gibson

Maxwell since 1987.

|

|

| photo

Mariana Cook |

|

photo Johannes Von Saurma

|

PREMIÈRE MONDIALE / WORLD PREMIER

Lire aux cabinets de Clara Gibson Maxwell

"Thoreau's Henhawk Visits Mexico"

A Participatory Film Screening of

Clara Gibson Maxwell's

39-minute Videodance/Social Documentary

To Program A Virtual or Live Projection/Discussion

Contact modafrance@compuserve.com

Clara Gibson Maxwell

(Choreographer-Dancer)

Romain Garioud (Cellist)

With Active Participation of Students from the

Cátedra Interinstitucional Cornelius Castoriadis

"This mixed-media treasure poetically and beautifully portrays the soul of Thoreau: ecology and ethics. Viewing it lightens the spirit while evoking thoughts of where we are and where we should be with Mother Earth and all her living things."

-Karen D 'Onofrio

"This was an ambitious project that really shone a light on Thoreau and some of his principles." -Eva Heinemann, Hi! Drama

Revolving around an 1859 excerpt from Henry David Thoreau's Journal: "What we call wildness is a civilization other than our own," Thoreau's Henhawk Visits Mexico is a 39-minute video of a choreographic/musical/video-projection/spoken-word performance by Mon Oncle D'Amérique Productions/Appalachian Springs Foundation Artistic Director Clara Gibson Maxwell, for a colloquium at the early 16th-century Casa de la Primera Imprenta de América (House of the First Printing Press in the Americas) in Mexico City, with the active participation of students from the Cáthedra Interinstitucional Cornelius Castoriadis (CICC) for this bilingual event.

Henhawk's soaring perspective is inspired by Thoreau's saying, "It's not what you look at that matters, it's what you see." CICC students wearing GoPro video cameras filmed the live performance from different angles and heights. This footage was incorporated into the initial edited version, which was projected the following evening at the Casa. Everyone then contemplated what these students had deliberately seen.

Formally (though also inextricably linked to thematic content), Henhawk is polytheamic: the equivalent for sight, here videographic, of what polyphony is for sound. From the introductory drone footage to the multiple mobile GoPro operators to the video projections (incorporating the viewpoints of projectionist, film characters, and green-screen footage of Clara, inset, contemplating these filmed human, animal, plant, and inanimate actors), to Clara viewing these projections of herself and others, upside down, in an extended yogic headstand pose during the performance, and passing by way of the live audience's and viewers' kinaesthetic responses to the dancer's expression and their visual experience of witnessing the dancer's and ambulatory cellist's calls and responses, Henhawk is multiplicative of embodied and technical gazings, explicit and implicit, inside and outside the reference frames of physical site, camera, and screen. We are thus invited to Thoreauvian wakeful contemplation of "what [we] see" and of the infinity of our ways of seeing.

Thoreau's views on Civil Disobedience were formed in part as a response to the Mexican-American War. Our 2017 event celebrating Thoreau's 200th birthday brought Thoreau to Mexico. One of the attendees, Ana Julia, who has worked with the Amuzgos, an indigenous people in Guerrero State, on their pirate-radio project in an area suffering from water-access issues, was particularly interested in Thoreau's involvement in native culture and civil disobedience. The audiovisual record of the postperformance student discussion with our artistic-technical team about the relevance today of Thoreau's views on art, nature, native peoples, somatic practices (yoga), and social change forms the emotionally gripping and thoughtfully fascinating final section of our new video.

The hen-hawk and the pine are friends.

The same thing which keeps the hen-hawk in the woods, away from the cities, keeps me here.

That bird settles with confidence on a white pine top and not upon your weathercock.

That bird will not be poultry of yours, lays no eggs for you, forever hides its nest.

Though willed, or wild, it is not willful in its wildness.

—Henry David Thoreau, Journal, February 16, 1859

of Hawk-on-a-Pine.jpg)

Kano Yukinobu (Japanese, ca. 1513–1575, Daitoku-ji Monastery, Kyoto) resident

Hawk on a Pine, 16th century. Medium: Two-panel hanging scroll; ink on paper

LEFT SCROLL: Minneapolis Museum of Art; RIGHT SCROLL: Metropolitan Museum of Art

CLARA GIBSON MAXWELL PLAYS SHAKUHACHI

AT DAITOKU-JI MONASTERY

ZUIHŌ-IN ZEN BUDDHIST SUBTEMPLE; DAITOKU-JI MONASTERY; KYOTO, JAPAN; OCTOBER 2018

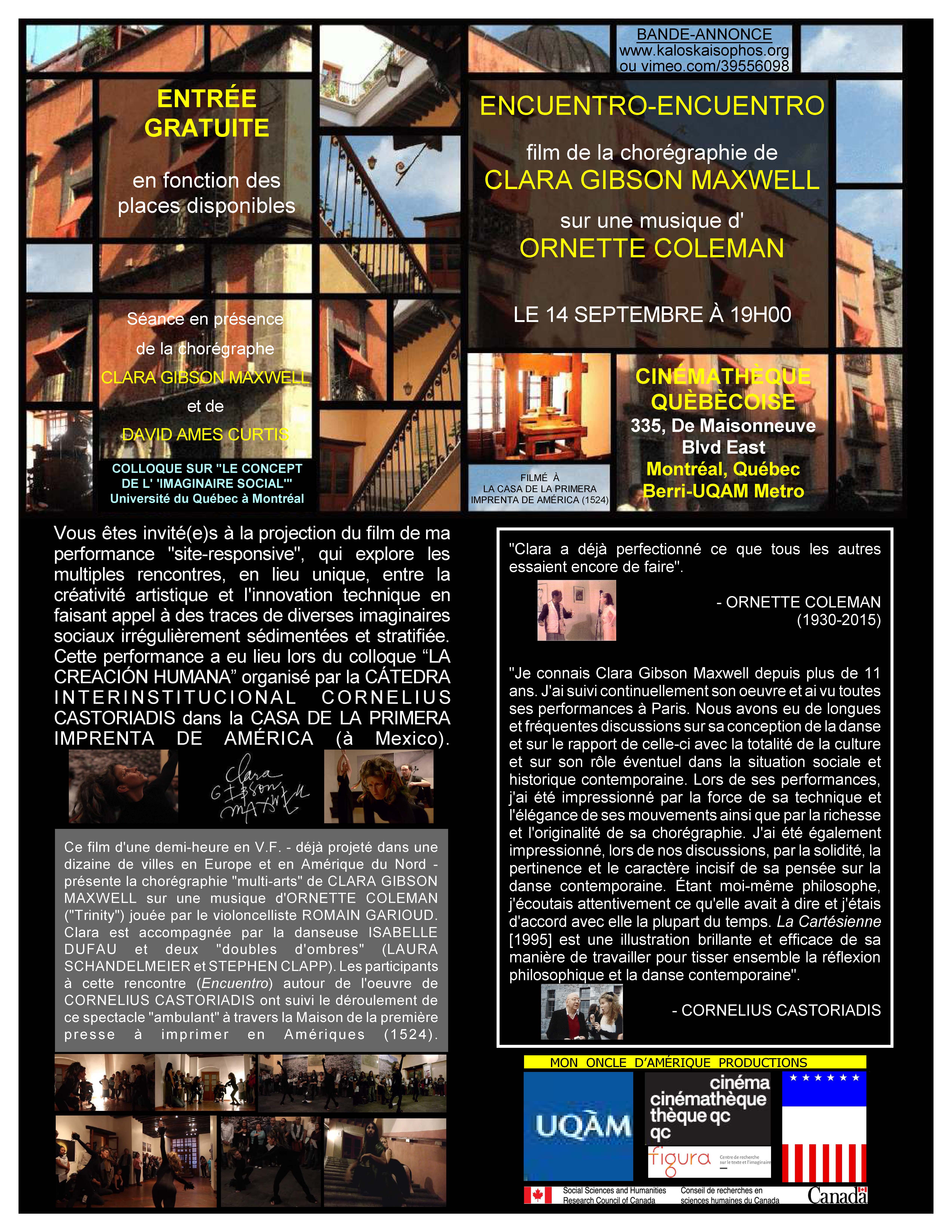

“ENCUENTRO-ENCUENTRO” (VIDEODANCE)

TWO PROJECTIONS IN KOREA

11 October 2018, 3:00-5:00 PM

Center for German and European Studies(ZeDES)

Building 303 Room 601, Chungang University, Seoul, Korea

시간: 2018년 10월 11일 오후 3-5시 장소 : 중앙대학교 303동 601호 (법학관) 주최: 중앙대학교 독일유럽연구센터 클라라 맥스웰(아팔라치아 스프링 재단), “Encuentro-Encuentro” 데이비드 에임스 커티스, “야만에서 무의미성으로, 무의미성에서 새로운 상상을 위한 투쟁으로: 지금 우리가 서 있는 곳에 대한 코르넬리우스 카스토리아디스의 설명

14 October 2018, 3:30-6:00 PM

City Museum of Seoul, Seosomun, Seoul, Korea

For the Seoul Media City Biennale (SeMA) 2018

시간: 2018년 10월 14일 오후 3:30-6시 장소 : 서울시립미술관 서소문본관 주최: 서울시립미술관, 2018년 서울미디어시티 비엔날레 클라라 맥스웰(아팔라치아 스프링 재단), “Encuentro-Encuentro” 데이비드 에임스 커티스, “야만에서 무의미성으로, 무의미성에서 새로운 상상을 위한 투쟁으로: 지금 우리가 서 있는 곳에 대한 코르넬리우스 카스토리아디스의 설명

“Encuentro-Encuentro” - une chorégraphie “site-responsive” et “multi-arts” de la chorégraphe-philosophe Clara Gibson Maxwell - explore les multiples carrefours de rencontre entre la créativité artistique et l’innovation technique en faisant appel, d’une manière apodictique et non pas discursive, à des traces de diverses imaginaires sociaux irrégulièrement sédimentées et stratifiées dans un seul lieu.

Cette performance participative et ambulatoire créée lors du colloque l’ “Encuentro - Creación humana” organisé par la Cátedra Interinstitucional Cornelius Castoriadis a eu lieu à Mexico, ancienne capitale aztèque, dans la Casa de la Primera Imprenta de América (1524), où cohabitent des signes et des spécimens de “nouvelles technologies” de communication de plusieurs époques et d’imaginaires différents :

• la tête en pierre du serpent à plumes Quetzalcoatl, inventeur des livres et des calendriers, récemment retrouvée dans les soubassements de cette Casa située près du Templo Mayor détruit en 1521 par les Espagnols ;

• une réplique de la presse typographique originale, la première au Nouveau Monde (1536), importée par les autorités pour imprimer des décrets royaux et des tracts religieux ;

• des fragments de fresques du seizième siècle peintes sur les murs de la Casa - encore une méthode de communication ;

• une presse typographique du XIXème siècle hébergée sur place au Musée du Livre ;

• un ordinateur qui fait entendre un extrait d’un texte du philosophe Cornelius Castoriadis sur la passion et les limites de l’informatique.

Nous vous proposons une projection de la vidéo (34 minutes), dont le montage est une extension, une élaboration et un affinement des démonstrations artistiques et philosophiques de cette performance, en particulier le principe de doublement (qui ne veut pas dire répétition) cher à Ornette Coleman, compositeur du morceau de musique sur lequel dansent les interprètes et leurs doubles d’ombre, exemplifiant et prolongeant corporellement la théorie musicale démocratique de cet inventeur du “Free Jazz” - l’ “Harmolodics”, qui accorde une valeur égale à l’harmonie, à la motion (ou le rythme) et à la mélodie.

http://vimeo.com/kaloskaisophos/bande-annonce-encuentro-encuentro

CONTACT: modafrance@compuserve.com

WHY

WWW.KALOSKAISOPHOS.ORG?

In

ancient Greek, "Kalos" meant "Beautiful" and

"Sophos" meant "Wise." We do not claim to be or to

incarnate "Beauty" and "Wisdom," but our creative

collective efforts are directed toward those "ends," motivated

and furthered by the love thereof. The love of Beauty and Truth is the

first condition of possibility for their imaginative re-creation, just

as the practice thereof gives one a taste of and for that love.

In the Funeral Oration from The History of the Peloponnesian

Wars (2.40), Thucydides reports Pericles declaring:

Philokaloumen te gar met ' euteleias

kai philosophoumen aneu malakias.

An initial (overly literal) shot at a translation:

For we love beauty, but with good purpose,

and we love wisdom in a way that does not make us soft.

The

English philosopher Thomas Hobbes had offered this translation c. 1628:

"For

we also give ourselves to bravery, and yet with thrift;

and to

philosophy, and yet without molification of the mind."

His

editor, David Grene, comments: "This is a magnificent

seventeenth-century sentence, but liable to misconstruction by a modern

reader. In our idiom the literal rendering is:

We are lovers of beauty, but with cheapness;

we are

lovers of culture, but without softness."

Grene

goes on to explain that Hobbes translated Thucydides' great work

"in order that the follies of the Athenian Democrats should be

revealed to his compatriots." Nevertheless, Hobbes the political

absolutist offered us this "magnificent seventeenth-century

translation" of his--one that admirably expresses the ideals of the

Athenian democracy, despite his contempt for them.

The twentieth-century philosopher Hannah Arendt also reflected--more

sympathetically, yet even more idiosyncratically than Hobbes did--on

this famous passage:

We love beauty within the limits of political judgment,

and we

philosophize without the barbarian vice of effiminacy."

In

her text "The Crisis in Culture," where this translation is

offered, Arendt's main concern was to reconcile "the

Greeks"--who, she believed, were cultureless--with Cicero and

Immanuel Kant by showing how "the Greeks" preceded these two

of her favorite thinkers in the linking of "politics" and

"art." But she also sought to highlight the differences

between "the Greeks" and, on the one hand, "the

Romans" (the latter are said to have originated culture) and, on

the other hand, "the barbarians" (the latter are said to be

viewed by the Greeks as softened by despotism)--not to appreciate the

possible connection between philosophy, democracy, and art in

ancient Athens, where this Funeral Oration was composed. Arendt thus

provides no hint that Pericles' Funeral Oration was spoken in Athens

amid a generation-long struggle of the democratic poleis

against the Spartan-led oligopolies of the time. The contrast the

Corinthians made elsewhere (1.70) between the hesitant and indecisive

Spartans, on the one hand, and the Athenians who saw no contradiction

between thought, feeling, and action, on the other, is missed entirely.

And, finally, she misconstrued the Greek "middle voice" of philokaloumen

and philosophoumen, speaking of the "love of

beautiful things" and "philosophizing" each as "an

activity" (action being one of her primary philosophical

categories), rather than as a a kind of self-transformative (and

society-transforming) process, wherein the collective passion for

democracy would be as important as any action undertaken by

individuals, great or otherwise.

The late social and political thinker, Cornelius Castoriadis, offered an

in-depth reflection upon the meaning of this phrase while criticizing

Arendt's interpretation thereof. It is worth quoting this discussion in

extenso, for here the intimate and crucial connection between

philosophy, democracy, and art is appreciated in full:

The substantive conception of democracy in Greece can be seen clearly in

the entirety of the works of the polis in general. It has been

explicitly formulated with unsurpassed depth and intensity in the most

important political monument of political thought I have ever read, the

Funeral Speech of Pericles (Thuc. 2.35-46). It will always remain

puzzling to me that Hannah Arendt, who admired this text and supplied

brilliant clues for its interpretation, did not see that it offers a substantive

conception of democracy hardly compatible with her own. In the Funeral

Speech, Pericles describes the ways of the Athenians (2.37-41) and

presents in a half-sentence (beginning of 2.40) a definition of what is,

in fact, the "object" of this life. The half-sentence in

question is the famous Philokaloumen gar met'euteleias kai

philosophoumen aneu malakias. In "The Crisis in Culture"

Hannah Arendt offers a rich and penetrating commentary of this phrase.

But I fail to find in her text what is, to my mind, the most important

point. Pericles' sentence is impossible to translate into a modern

language. The two verbs of the phrase can be rendered literally by

"we love beauty . . . and we love wisdom . . .," but the

essential would be lost (as Hannah Arendt correctly saw). The verbs do

not allow this separation of the "we" and the

"object"—beauty or wisdom—external to this "we."

The verbs are not "transitive," and they are not even simply

"active": they are at the same time "verbs of

state." Like the verb to live, they point to an

"activity" which is at the same time a way of being or rather

the way by means of which the subject of the verb is. Pericles does not

say we love beautiful things (and put them in museums), we love wisdom

(and pay professors or buy books). He says we are in and by the love of

beauty and wisdom and the activity this love brings forth, we live by

and with and through them—but far from extravagance, and far from

flabbiness. This is why he feels able to call Athens paideusis—the

education and educator—of Greece. In the Funeral Speech, Pericles

implicitly shows the futility of the false dilemmas that plague modern

political philosophy and the modern mentality in general: the

"individual" versus "society," or "civil

society" versus "the State." The object of the

institution of the polis is for him the creation of a human

being, the Athenian citizen, who exists and lives in and through the

unity of these three: the love and "practice" of beauty, the

love and "practice" of wisdom, the care and responsibility for

the common good, the collectivity, the polis ("they died

bravely in battle rightly pretending not to be deprived of such a polis,

and it is understandable that everyone among those living is willing to

suffer for her" 2.41). Among the three, there can be no separation;

beauty and wisdom such as the Athenians loved them and lived them could

exist only in Athens. The Athenian citizen is not a "private

philosopher," or a "private artist," he is a citizen for

whom philosophy and art have become ways of life. This, I think, is the

real, materialized, answer of ancient democracy to the question about

the "object" of the political institution. When I say that the

Greeks are for us a germ, I mean, first, that they never stopped

thinking about this question: What is it that the institution of society

ought to achieve? And second, I mean that in the paradigmatic case,

Athens, they gave this answer: the creation of human beings living with

beauty, living with wisdom, and loving the common good.

REFERENCES:

Thucydides.

The Peloponnesian War. 2 vols. Trans. Thomas Hobbes. Ed. David

Grene. With an introduction by Bertrand de Jouvenel. Ann Arbor: The

University of Michigan Press, 1959.

Hannah

Arendt. "The Crisis in Culture." Between Past and Future:

Six Exercises in Political Thought. New York: The Viking Press,

1961.

Cornelius

Castoriadis. "The Greek Polis and the Creation of

Democracy" (1983). Philosophy, Politics, Autonomy. Ed. David

Ames Curtis. New York: Oxford University Press, 1991.